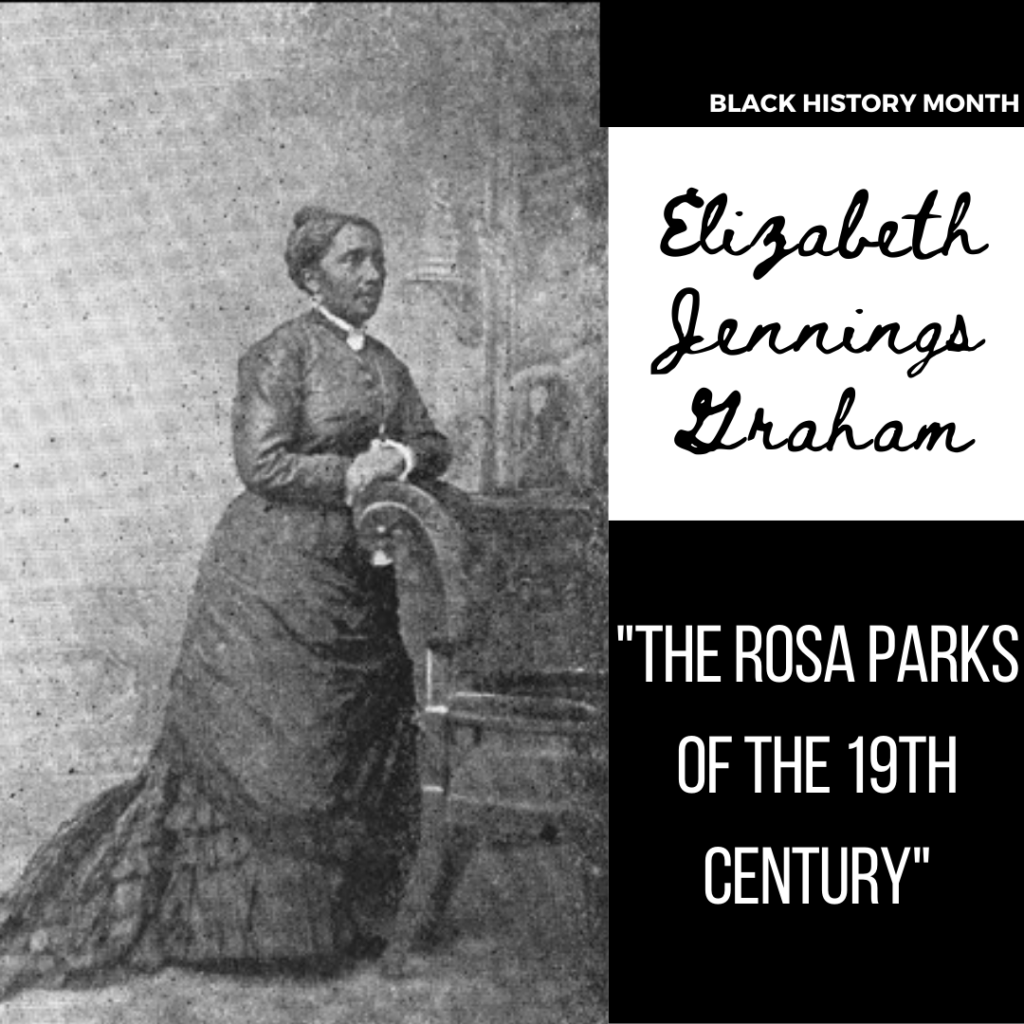

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (March 1827 – June 5, 1901) was an African-American teacher and civil rights activist, who challenged segregation on public transportation, a full 100 years before Rosa Parks did so. In 1854, she won a lawsuit against New York’s Third Avenue Railway Company for ejecting her from a streetcar because she was African American. The case led to the eventual desegregation of all New York City transit systems by 1865. She is known as “The Rosa Parks of the 19th Century”.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was born free in New York City to Thomas and Elizabeth Jennings in either 1826 or 1830 (both years are specific to her Death Certificate and 1850 Census, respectively). The specific day and month of her birth are unknown. Her parents were both prominent members of New York City’s small African-American middle class and her father was the first African American to hold a patent in the United States. Additionally, he was involved in many social and religious organizations and was one of the founders of New York’s Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Like her father, Graham was involved in many social and religious organizations, most prominently as a church organist. She, and her friend Sarah Adams, were on their way to the First Colored American Congregational Church on July 16, 1854, when she tried to board a streetcar of the Third Avenue Railway Company which at the time only allowed Euro-Americans as passengers. She was given permission to ride the streetcar, but the conductor told them, if any Euro-American passengers objected, “You shall go out or I’ll put you out.”

Jennings who wrote about the incident shortly after, said she told the conductor,

“I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York, did not know where he was born and that he was a good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.”

Replying that he was from Ireland, the conductor tried to haul Jennings from the car. She resisted ferociously, clinging first to a window frame, then to the conductor’s own coat. Continuing to drive, with Jennings’s companion left at the curb, he soon saw backup in the figure of a police officer, who boarded the car and pushed Jennings, her bonnet smashed and her dress soiled, to the sidewalk.

Graham’s forcible removal from the streetcar caused a massive protest against the streetcar company by members of New York’s African American community and others who felt she was unfairly treated. Her letter detailing the incident was read in church the next day; supporters forwarded the letter to The New York Daily Tribune, whose editor was the abolitionist Horace Greeley, and to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which both reprinted it in full. Meanwhile, her father hired an attorney and future 21st President Chester A. Arthur to sue the Third Avenue Railway Company on his daughter’s behalf. At the time, New York City and New York State had no laws regarding segregation on streetcars. Consequently, the court ruled that it had been illegal to forcibly evict Graham solely because she was African American, and awarded her $225 in damages. Her case itself did not lead to total desegregation of all streetcar lines, but it did set a precedent for future trials.

After the trial, Graham continued her career as a church organist and her career as a teacher. Later in life, Graham opened a kindergarten for African American children in her home. The kindergarten operated from 1895 until her death on June 5, 1901. Elizabeth Jennings Graham was buried in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery, along with her son and her husband.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was a pioneer in desegregation and education for African Americans in 19th century America. Her legacy lives on and continues to inspire.